In nature’s infinite book of secrecy, a little I can read. – William Shakespeare

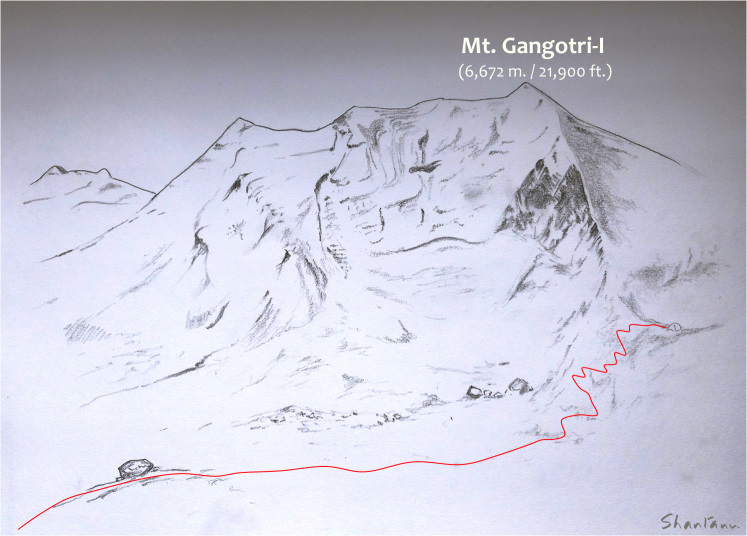

Four of us – my friend and I guided by two route guides – were climbing a very steep snow slope to gain the ridge between Mounts Gangotri-I and Rudugaira. We had decided to pitch our Camp-2 in the saddle on the ridge. It was to be our summit camp located at around 5,790 m. / 19000 ft. from where we were going to attempt reaching the summit of Gangotri-I (6,672 m. / 21,900 ft.). It was some time in the afternoon, and we had just walked across a long plateau beneath the steep slope, with the sun blazing down on us. The heat was appalling. That heat, reflected from the slope on our left and the surface of the plateau itself, made our world a furnace. The snow had turned to slush and each step sank in, turning the trudge into awful drudgery. The climb up was no different, the only difference being that now we actually stamped each step in to ensure that we did not slide down as the disturbed snow tended to break loose. Sometimes it felt like I was sliding down one step for every two steps I took up. And just when I had begun to think what probably all mountaineers tend to think at some point – ‘why did I get into this?’ – I had one of those intriguing experiences that happens in the world of adventure.

About two-thirds way up, bent over in the classic pose of mountaineers with one hand resting on the ice axe and the elbow of the other resting on my knee as I tried to catch my breath, my eyes fell on a… spider! There in that vast snow and ice ’scape, amidst snow granules that glittered in the harsh sun, I saw this arachnid moving around slowly. I had read that insects and arachnids tend to get carried away from their usual habitats lower down by strong winds to the lofty heights of snow clad mountains. Many of them then survive for some time feeding on the bits and detritus of organic matter that similarly get transported by strong winds. Now that is explaining the why and how of things. But our minds are at times more fanciful and go beyond the dry factual aspects of otherwise wonderful things. For encountering a spider just below 19,000 ft. was quite astonishing if you think about it! And picture my situation at that time – I had sweated through a hot day which was yet to conclude, my pack weight seemed to be increasing with each step I took and I was questioning my sanity in having got sucked into a senseless pastime called mountaineering. And there was the spider. Brought up on inspiring stories of great Indian kings and princes, I remembered the tale of Maharana Pratap who for years resisted Mughal forces through a series of battles. After a battle that he lost, Maharana Pratap was taking refuge in a cave in a forest, his self-confidence and will to continue to struggle gone. It was then that he saw a spider struggle to build its web, falling again and again to the floor when stray gusts of wind broke the strands that it had painstakingly slung across the walls of the cave. The message to the Maharana was clear. And legend has it that he left the cave with renewed hope and energy and went on to win his next battle.

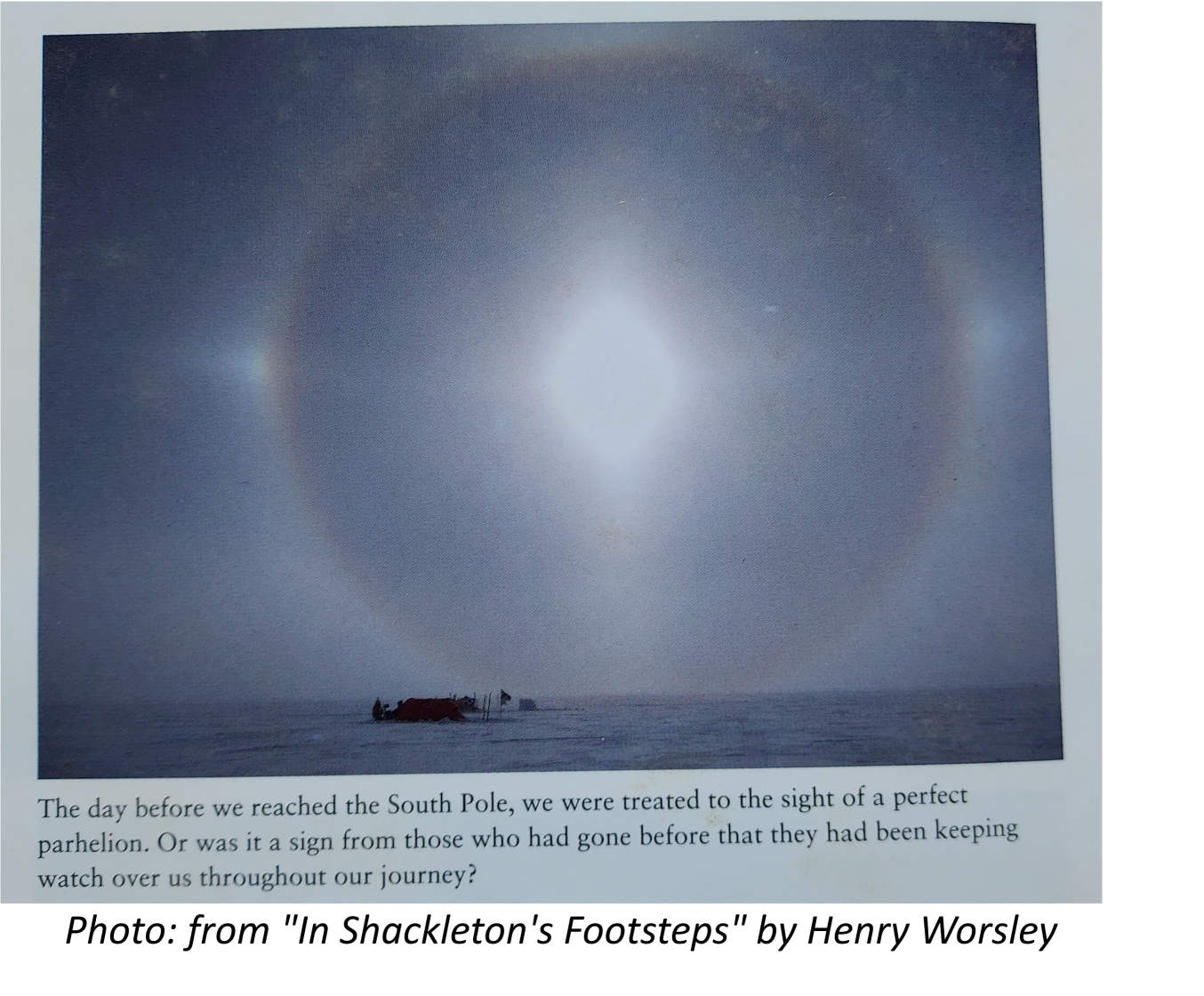

Some experiences in the world of adventure can also appear to be mysterious. In the book “In Shackleton’s Footsteps” that recounts the expedition of three men to the South Pole in 2009, author Henry Worsley writes, “I do not consider myself a particularly spiritual person but, looking back, I still feel that when I saw the snow petrels on the Ross Ice Shelf and the parhelion* the day before we finished the journey, these were signs that something had been keeping an eye on us. Of course, my interpretation of those two events could be put down to extreme exhaustion and heightened emotions but at that time I thought differently, and still do.” The photograph above is from the book mentioned above.

(*Parhelion: a parhelic circle, i.e., a solar halo, caused by the diffraction of light by ice crystals in the atmosphere, with the sun at the centre and with scups of light or ‘sun dogs’ dotting the four quadrants of the circle)

But I have a very poignant story to relate from something that happened on an earlier mountaineering expedition.

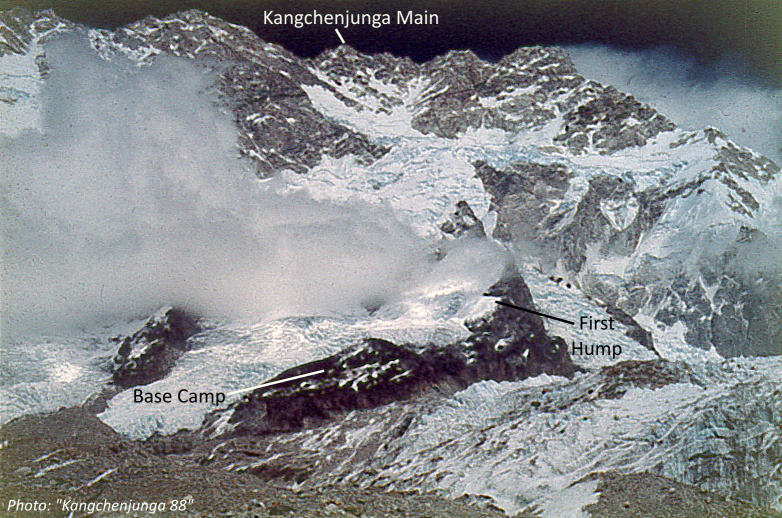

The above photograph was taken from a spot on the Upper Icefall on the SW face of Kangchenjunga, the world’s third highest and India’s highest mountain at 8,586 m. / 28,169 ft. We were attempting the peak in 1988, the first peak climbing expedition to an eight thousander** from our country that was fully organised by civilians. Our Camp-2 can be seen as three dots on the horizontal section of the ridge that drops down on the right. I had seen some beautiful sights when on the mountain. One of the strongest memories I have is of the extraordinary vista spread around and below me in the middle of a moonlit night while surviving an 8-hour storm that had winds that made standing impossible. Our tent at Camp-3 (6,850 m. / 22,500 ft) had collapsed and my tent mate and I were about to crawl to another tent when I glanced around and saw the whole landscape of rock and ice and snow laid bare of all clouds and mists and that glowed dully in the moon light with a few little pin pricks of sparkle here and there. It was beautiful beyond words. The rugged terrain and the immense danger that we were in created a mysterious and forbidding aura. Stark beauty can have remarkable impact on one’s psyche, and I remember how reluctant I was to let go of that vision even as my hand clutching my ice axe started freezing and the wind continued to howl around me.

(** There are fourteen mountains in the world that rise above 8000 m. above sea level, i.e., their summits are in the ‘death zone’ where the atmospheric pressure is inadequate to sustain life over extended time. Climbing an eight thousander is considered to be a formidable challenge. You can read more about them here.).

Later on in the expedition, I was accompanying Charuhas Joshi down to Base Camp (BC). Charu had returned from his summit attempt, the expedition’s first of the two attempts we made. He had to turn back short of the summit because of adverse weather conditions that had resulted in his fingers and toes getting frostbitten. His had been a remarkable push that took him beyond the enigmatic 8000 m. mark. I had accompanied him from Camp-2 and it had been an onerous task of pulling out our fixed ropes buried under fresh snow and where the indomitable Charu had displayed incredible resilience by climbing down virtually independently despite having frozen fingers. Below Camp-1, on top of the ‘First Hump’, as I waited for Charu to catch up on the rope that I had just pulled up, I suddenly came across a lone butterfly flitting around. We must have been at around 5,790 m. / 19000 ft. I remember feeling a bit sad for the butterfly and wondered if the storm of a few days back had blown it over to our mountain.

Upon reaching BC, Charu was given immediate medical care by our BC doctor and I retired to a tent to recoup from having spent time at high altitude. The next morning, we heard the heartbreaking news of our Deputy Leader, Sanjay Borole, having succumbed to hypothermia near Camp-2. Several factors including exposure to the 8-hour storm, subsequent stay at almost 7,300 m. / 24,000 ft. and fresh powder snow raining down on him at the base of a cliff contributed to the fatal effect on him. This had happened at the end of day preceding the day I saw the butterfly. And I couldn’t help but connect the ethereal presence of such a beautiful creature with the passing away of a courageous and talented soul.

I know the following quote refers to a different context but I can’t but still think of quoting it here.

‘The best people possess a feeling for beauty, the courage to take risks, the discipline to tell the truth, the capacity for sacrifice. Ironically, their virtues make them vulnerable; they are often wounded, sometimes destroyed.’ -Ernest Hemingway

What a coincidence! I just returned from Sandakphu after getting a beautiful view of Kanchenjunga range from Tumling. High altitude are both beautiful and lethal as I saw in Sikkim.

Coincidences too, I guess, can be trmed as ‘strange’ sometimes, right?! Well, lucky you. The Singalila Ridge is the one that drops down from the Kangchenjunga massif on which Sandakphu is located…

Thanks!