Do that thing that we fear and the death of fear is certain – Ralph Waldo Emerson

This post is about intense fear – that raw, mind numbing feeling that leads to total paralysis. The one time I have experienced it was also when I was fortunate to have been able to tackle that state of mind and continue to do what I had set out to do. It had brought me face to face with my own self where I ended up questioning my skills, my ability to take risks, the source of my happiness and, yes, my goals (oh I can see folks smiling away to glory – goals! It all so often comes down to ‘goals’, right?!)

Come winter rock climbers in most of India emerge from monsoon hibernation, grab their gear stored in lofts and cupboards, and scoot into the hills to start embracing the vertical world of hard rock. I have used all my ‘vacation times’ like Diwali and Christmas to hike or climb. So many of my “31st” parties (minus liquor!) have been in the lap of nature, either on a fort or at the base of a pinnacle in the Sahyadri. And ‘Tel Baila’ has occupied a special place in my life and in my psyche.

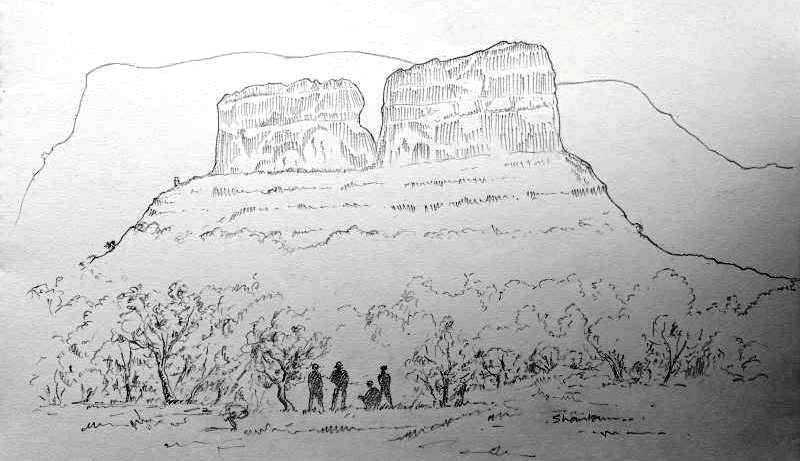

‘Tel Baila’ is a spectacular dyke situated close to the edge of the Deccan plateau on the border of districts Raigad and Pune, hundred odd kilometers south of Mumbai. I have lost count of the number of times I have been there. My visits have been for a variety of reasons – hiking, rock climbing, outdoor management development programmes and even an ad film project! This is also where I broke a leg in a climbing fall, froze in fright just a few feet above the ground and managed to overcome the resultant fear…

Love at first sight!

It was in 1986 that I first saw Tel Baila, and it was love at first sight. ‘The sight of the massif hit us like a physical blow’ is how I have described its impact in an article that got published in the magazine ‘Caravan’*.

As a youngster in mid-twenties then, I had had a blast on this beautiful dyke in the Sahyadri. That was also the first time that I saw crag martins (a.k.a. Eurasian crag martins) and dusky crag martins from up close as they flew in at twilight to settle in nooks and crannies on the sheer walls, the only birds that either roosted or nested on those precipitous walls. And I remember when, tethered to my station with a camera shooting the action on the opposite wall, I had seen a hovering shikra at eye level right next to the wall. The whole experience and sheer aesthetics of the geological formation and its surroundings has drawn me to this dyke ever since that first sojourn. There is one particular route, the northern edge of the dyke that faces the village of Tel Baila, which I had not managed to climb on the multiple attempts that I had made. It is not a difficult route, but those were the days when we struggled with ‘resource constraint’ (not enough equipment), old rusty bolts hammered by previous climbers into ancient friable basalt, and lack of adequate skill, experience and physical fitness.

The fall

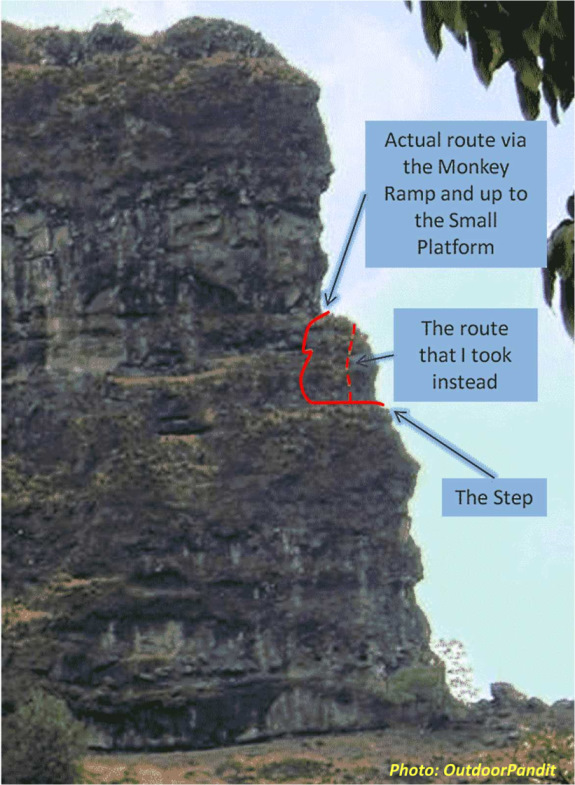

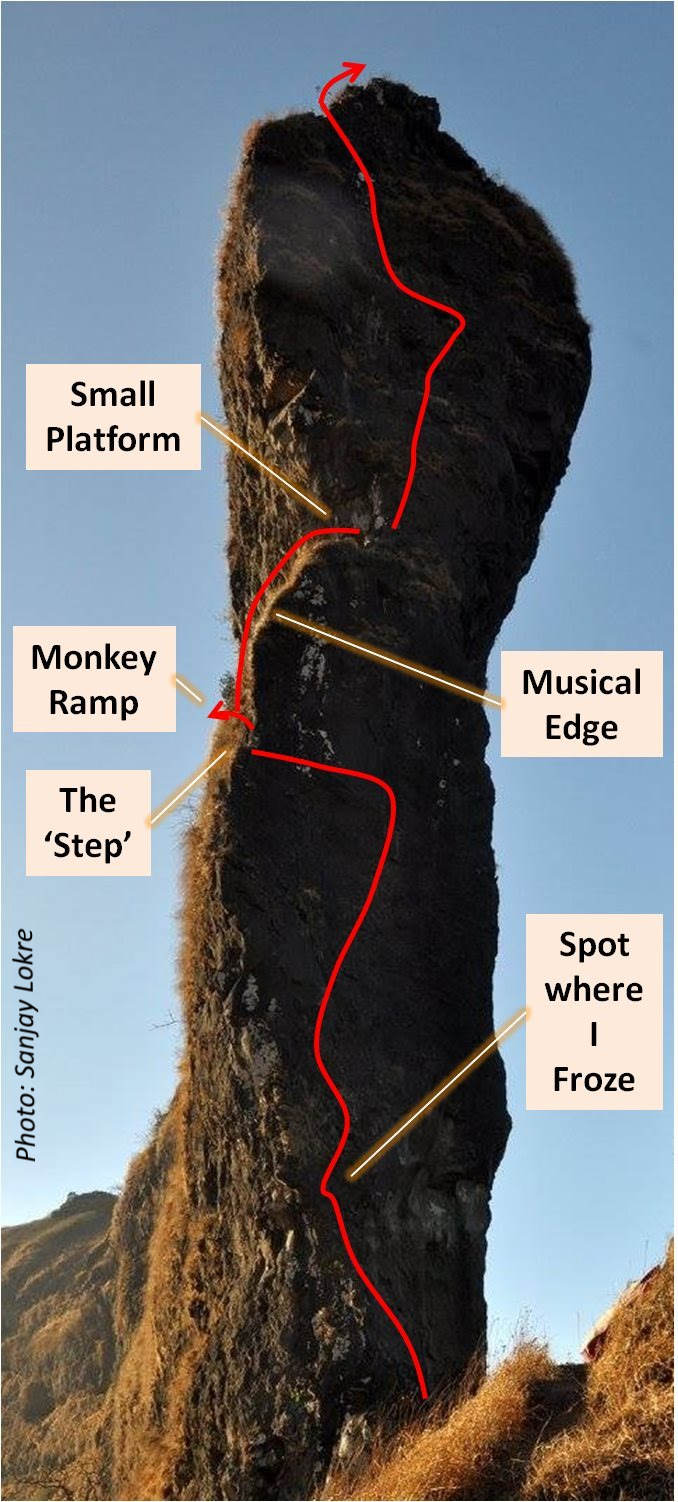

My most critical climb happened in the early nineties when I led up that north-edge route and reached the halfway point. From there the route veers to the left, the eastern face of the dyke. It is actually a narrow ramp that monkeys – rhesus macaques – regularly use. Somewhere along that ramp I was supposed to start up again to gain a small platform where the vertical edge of the dyke eases out a bit. I had left the ramp at the wrong place and climbed up only to hit the knife-thin edge of the dyke, just below the platform. Climbers in this region have developed the habit of sounding the rock that they are about to climb to check its solidity and reliability. The rock that I was facing above me sounded musical against my taps – I could have played a tune on it! That freaked me out.

I tried to haul myself up but chickened out when it came to levering myself up (the classic ‘mantelshelf move’) because there is a point when the climber tends to exert an outward pull during that move. I had suffered a fall in the past in the Mumbra Hills when a hand-hold that I had pulled on had sheared off a slab. The resulting twenty-foot tumble had horrendously scraped my back and arms and it had taken a total of eleven stitches to deal with my scalp injuries. The memory of that fall sparked off stark visions of what would happen if this musical edge of Tel Baila broke off under my pull. I was tired, and my brain could not think the physics required for appropriate body kinetics to minimise that outward pull, so finally I gave up. I announced to my belayer that I was climbing down and started doing so, when I lost my footing and fell. My right foot landed on a ‘step’ before the rope between me and my belayer could come taut. I remembered how I had marveled at the piton that had held such a fall! Before I crawled up to that same ‘step’ to rest, my ankle had ballooned up. After I had rappelled off to the base, a team member had to piggy-back me down to our motorcycles.

As an interesting aside, when the doctor in Pune looked at the x-ray of my ankle, he asked me about a previous fracture on the same leg. When I said I had never had a fracture before he showed me where a hairline fracture in my tibia had healed. I had to wrack my brains before I remembered. I had ‘sprained’ that ankle exactly ten years back when clambering down a long scramble while dropping down from the Deccan plateau to go to fort Raigad in the coastal plains. Nobody had thought ‘x-ray’ after I had hobbled across the threshold of our flat upon my return, probably because the ankle/leg was ‘usable’ and it was not the first time that I had sprained an ankle. Ah well. Imagine how many such fractures there must be around that have healed well without ever having got ‘treated’!

‘Getting stuck’ and ‘getting unstuck’

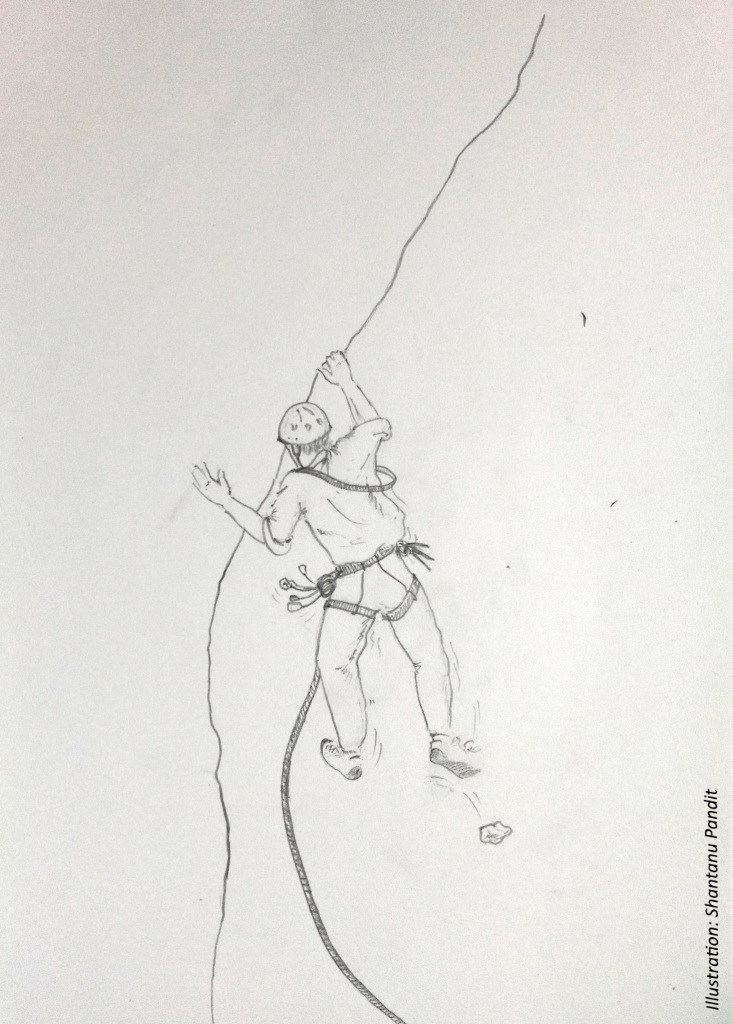

I went back to Tel Baila the next year. It was “31st ”! This time I was with two friends, Shirish (Buddhya) Sahasrabuddhe and Pushkaraj (Pushkya) Apte. The former had already climbed the north-edge route and was with us to help us stay on the correct route. And the latter was in the same boat as me – multiple attempts and no success. I started lead climbing early in the morning. It was windy and I was wearing a wind-cheater that crackled as its loose folds flapped in the wind. About fifteen feet above Pushkya, I had still not got any protection piece in through which to thread the rope, primarily because of the quality of the rock. What that meant was that if I fell I would fall a long way, before Pushkya’s belay-device would hold my fall. And then a foot-hold came loose and clattered down. As the weight suddenly came on my hands, my fingers gripped the thin edge of the dyke.

And I froze, waiting for the fall that I thought would inevitably come. But it all held, and I hung on there. And hung on. And hung on. Unable to move a muscle. It was cold, and my tensed up muscles started tiring. A climber must breath and a climber must keep moving. Stuck to one place tires muscles unnecessarily. I didn’t want to go down – that would have meant admitting defeat. But for the life of me I couldn’t move up! I remember distinctly how wooden I felt, my heart laden and unwilling to support an upward move. The classic signs of a mind frozen with fear. Not, I guess, mere fear but true terror that paralyses. And then there was shame and utter frustration. Both Buddhya and Pushkya tried to guide me up but in vain. Finally Buddhya gently said that I had been up there for twenty minutes and it is best that I come down while I had the strength to do so. I knew how my fingers would eventually simply open up by themselves. I quietly retraced my steps down those fifteen odd feet that I had climbed and sat suitably humbled at the base before setting myself up to belay Pushkya. He went up smoothly to the spot from where the route traverses to the ‘step’ on which I had broken my bone a year back.

As I let the rope out, a thousand thoughts assailed me. Was I never going to get over the fear of falling? Was this ‘it’ for me? Will I never be able to climb at height? Would my terror turn to a horror of climbs?! And somewhere there I fought back, realising that if I don’t climb up after Pushkya and lead the next pitch then I will probably never go up on such climbs, ever. Ever?

I remembered all the times when I had been up on heights on vertical rock, the vast ’scapes spread around one’s vantage point, the distinctive hush of the climber’s world, the wonder of wondering what the birds and monkeys must think of us, the feeling of oneness with the world, the indescribable feeling of camaraderie with one’s climbing mates and the quiet self-sufficiency of outdoorspeople…

That was a reality that I was loath to leave without a fight. I was very clear that I wanted to continue to climb, not because I hungered for summit-achievements and recognition, but simply because the climber’s world was my world. There was no need for elaborate explanations, no need to go over what ifs and whys. There was no question about it.

“If I don’t climb up after Pushkya and lead the next pitch then I will probably never go up on such climbs, ever”. Unthinkable!

When Pushkya asked me if I would like to come up after him or should Buddhya do so instead, I grabbed the end of the rope and tied myself in. While Pushkya pulled in the slack between us I stilled my fluttering mind. It makes a world of difference when there is a top rope – if you peel off then at the most you swing like a pendulum but there is no ‘fall’ as such. So it was easy to climb with Pushkya belaying me from above. I think this secure mode of climbing helped me get back into the required state of mind. There was absolute reliance on my climbing partner and equipment. My battle was my own, inside of me, and I think what worked for me was to not worry about falling off but just concentrate on the rock in front of me and shift my body one move at a time. I have always experienced a rare exuberance while climbing rock, and this bit of climbing put me back on an even keel, so to say. By the time I reached Pushkya, I was in an overjoyed state of new found confidence, not to speak of immense relief for having found back my climbing feet.

At the ‘step’, we exchanged positions and I started leading from there onwards. I shuffled my way across the monkey’s ramp, and came to the spot described by Buddhya from where I had to head up. That vertical patch had a small overhang which was just the perfect challenge for my high spirits at that time. Soon I was on the small platform, safe and sound, with that specific feeling that only the great Wodehouse can describe: ‘The snail was on the wing and the lark on the thorn – or, rather, the other way around – and God was in His heaven and all right with the world’! With the milk of human kindness sloshing around in him (to continue in the Wodehouse vein, now that I am at it!), Pushkya very generously allowed me to lead on and I shot up like a caged animal let out in the wild. To put it in perspective, the climb from that small platform involved more of ‘trad climbing’ that requires methodical use of small rope ladders and other equipment than actual climbing skills, but it helped me use all the pent-up energy that had been unleashed. It helped that there were strategically placed expansion bolts on the route which I used. I reached the top and belayed Pushkya as he followed, retrieving the odd piton and choke-nut that I had placed on the way

Back at the base

Back at the base, while we were coiling up ropes, Buddhya said, “So at last you two are done with this route! I think we can call it the Apte-Pandit Trophy!” In our little circle, we still refer to it by that name.

(Note: naming of any route is done by the team that climbs it first, so our privately discussed name cannot be official)

31st Party!

We were joined by two more friends and there, under the stars, with the cold Tel Baila winds blowing, we celebrated the end the year and welcomed the new one. Pushkya played his flute, a raconteur friend kept us in splits, and it was all I could do to not get up and dance around in unbounded joy and relief. I am sure someone looking at us from outside would have seen similarities between our merrymaking and the last scene in every Asterix book. Except that instead of a Cacofonix tied up on a tree, they would have seen my Terrorix tied up on the rocks!

Fear & After

It would be good to make an effort to understand what must have happened to me on that day, and what helped me overcome my state of being stuck.

Why I became stuck

- An incident sparked off a reaction in me (one of my footholds getting dislodged)

- After that incident my immediate recall was that of a previous fall on the same route high above when I had broken a leg

- Losing self-confidence: the chances of falling depended upon my climbing ability, because without a piece of protection between me and my belayer I would have fallen far had I peeled off

- My refusal to accept my inability at that time and terming it as ‘defeat’

- Not recognising my friends as my supporters and sympathizers

What helped me become unstuck

- No comment from my friends that could be construed by me as derisive – any such perception on my part would have had me go into a spiral; I think my friends were very sensitive and careful when they tried to guide me

- My ability to eventually calm down and realise my situation

- Buddhya’s quiet voice helped calm me, and helped me focus on his suggestion instead of the thousand things that my mind was prey to – and that helped my mind see the sense in what he was saying

- I moved when I still had energy to do so – had I stayed stuck for some more time I would have lost the last remaining energy to even climb down, which would have been disastrous

- My interest in the larger goal of the current project – that the route needed to be climbed, and if I was incapable then there was Buddhya to help Pushkya climb it

- I am not besotted with the idea of ‘bagging a peak at any cost’; I knew about unfortunate incidents throughout the world where unsafe decisions and practices had resulted in disastrous consequences

What helped me go back up

- The great outdoors! It is a place where confronting oneself seems safe and easy, non-threatening

- Calm support and empathy by my friends – I felt safe despite having had my vulnerability surface

- Being in touch with my larger goal – I wanted to keep climbing

- Being aware about the multi-dimensional benefits and rewards of climbing at height

- Being aware that this ‘failure’ was just one more in a many unsuccessful attempts in the past, but that there had been successful attempts too on other routes on other pinnacles

- *(For the eighties article in ‘Caravan’, click here.)

Wonderfully written!

Thanks, Sonali! It’s a place to inspire good thoughts 🙂