* Good intentions need the complement of robust team processes for effective teamwork *

“I had chosen this organisation because of its well known work ethic. But if this is how current recruitment is happening then I will have to seriously think about staying on!”

That dramatic announcement was made by a senior level executive at one stage in an outdoor management development programme I was conducting. It was nearing midnight and our reflection session had far exceeded the expected time duration. The reason was obviously strong and relevant enough for the participants to still be engaged so passionately – this is the dream of every facilitator, that participants drive debrief sessions! Frankly, I too was a bit baffled as to how to consolidate the discussion and end it meaningfully though we may not have any conclusions on points of debate. And then it happened. One of those inspiring moments of clarity descended on me and I raised my hand to call everyone’s attention. But before I go into that, it is important for you folks to have an idea of the events that had led the group to this brouhaha.

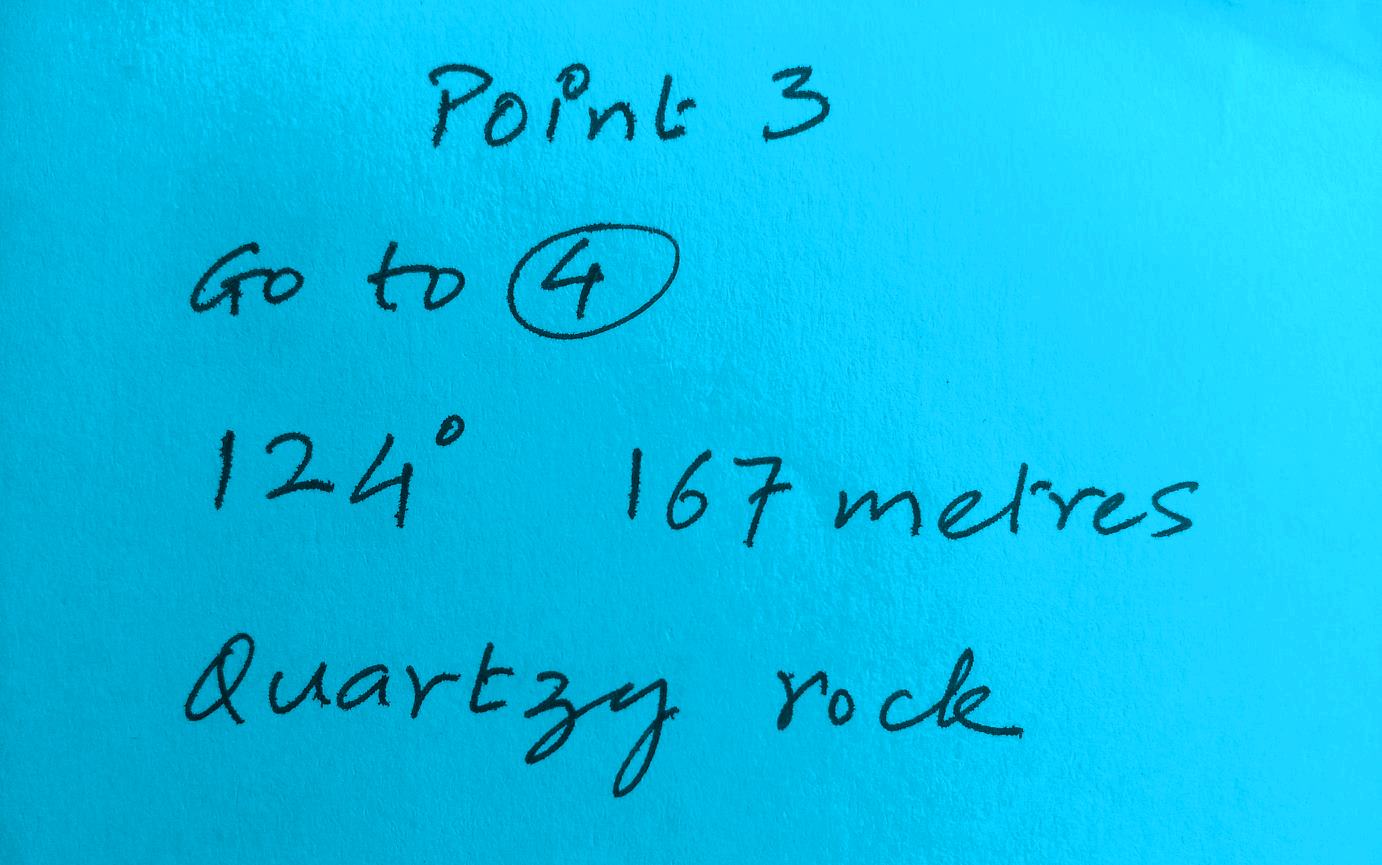

I was conducting a 3-day programme for a business organisation in an outdoors setting – tented campsite set up in the middle of undulating scrubland dotted with trees, with some hills just a little distance away. Participants were from across levels. Programme objectives touched upon a few specific areas under the broad objective of ‘team building’. We had progressed through a succession of activity-based experiences interspersed with debrief sessions – formal forums created for introspection and shared reflection. While we had concluded some discussions which could be used by participants to evolve action plans in their workplace, we had also parked a few thoughts for further exploration. On Day-2 the group started on a navigation exercise (nav-ex) just as our campsite became awash in glorious twilight. The group was split into randomly formed teams, each comprising of 4-5 persons. Using a simple magnetic compass and pacing technique (to walk known distances), each team was to walk on a distinctive route picking up chits with clues to successive points. All knew that there was a ‘treasure’ at the end of the exercise.

One of the programme objectives – inter-team networking – inspired me to throw a spanner in the works that prevented teams from smoothly sailing through their respective routes. In the middle of the exercise, I had mixed up the locations of clues which required teams to talk to each other and exchange clues to be able to get back on track. I had ensured that this mix-up was located centrally where teams were close to each other and could easily overhear each other’s conversations, which was supposed to help them quickly assess the situation, facilitate exchange of clues and proceed further. Whenever I have arranged such a mix-up teams have usually realised what has happened and moved on. Sometimes teams have held on to a wrong clue that they have found and tried to negotiate for a bigger share of the ‘treasure’.

And that is exactly what happened with one team on that programme that day! I had observed that this team had been particularly slow right from the beginning. It is easy for all teams to hear about the progress being made by others as people shout out across distances and celebrate the finding of a chit with hoorays. So, this team knew that it was slower than all other teams. By the time this team arrived at the location with the wrong clue, other teams were already talking to each other and had just started exchanging clues. While this was happening, members of the tardy team were informed of the situation and told to be ready to exchange their clue with some other team who must have their clue. But members of the tardy team started negotiating for a bigger benefit at the end of the exercise as a precondition to exchanging clues. All reasoning failed to convince them, including a simple ‘oh this is a team building programme so this mix-up was done obviously on purpose’. At times the discussion turned acrimonious. The teams that had exchanged clues soon finished walking their respective routes only to hit the next block: all teams were required to collect together their clues and solve a ‘puzzle’ in order to arrive at the location of the treasure which was obviously meant for the whole group. But now they were short of two sets of clues, one belonging to the tardy team and the other to the team that they were supposed to exchange their mixed-up clue with. The impasse continued well into dinner time before things finally moved ahead. But the usual celebration that happens upon finding the treasure never happened. The unreasonable demand that was negotiated for hung like a cloud over the group.

I was ready to call it a day and have the debrief session for the nav-ex after breakfast the next day but the group, especially its senior members, insisted that we have it after a quick dinner. It was a sombre group that assembled beneath a big jambhool tree (Syzygium cumini a.k.a. Malabar plum, black plum, jamun*). We sat in a rough circle, our faces lit by a couple of gas lamps placed at the centre. I urged the group to speak holistically of their experience. Some points are worth mentioning:

- People were very supportive of each other as they struggled to use newly acquired skills (how to use a compass and pace out given distances) – this was something that needed to be seen more at the workplace as even skilled and experienced people struggle with complex realities.

- The sheer joy felt as each clue was found was very energising, and it would help if team members celebrate successes at key milestones in a project.

- There was ambiguity about whether the ‘treasure’ was meant for the whole group – that became apparent only after the first few teams had collected all their clues. The ambiguity at the start had encouraged the natural feeling of competitiveness, a trait that everyone agreed was a good trait when used at the right time.

- There is a need for someone – usually the leader of a team – to be firmly aware of the big picture and ensure healthy competition – ‘there is a time to compete and there is a time to collaborate’.

The discussion finally veered towards the topic of the heated negotiation in the middle of the nav-ex. The four team members, all coincidentally young executives, were put on the spot. It was very clear that they had realised how unreasonable their stance had been when they had dug in their heels despite evidence of the need to collaborate. They admitted as much immediately. But there were some people who wanted to know why they had taken such a pointless stance at all in the first place. The four tried to articulate a few reasons, including how they wanted their team to win. Their stance was seen as detrimental to ‘team spirit’ that was expected of everyone. The four argued that this was a game and all they wanted to do was to have their team excel and that they had anyway been late in arriving at the midpoint and they saw this exchange of clues as an opportunity to catch up with the other teams. This was countered by the others and the discussion soon became heated where finally one senior executive made that dramatic statement quoted at the beginning. He questioned the way business schools and other professional courses were grooming their students and wondered if competitiveness was all that mattered to today’s professionals. That is when things took a turn that can be truly labeled as ironical.

One of the four slowly admitted that he actually did not want to negotiate but felt compelled to support his team’s decision so had not voiced his opposition to negotiating for a bigger share. Another person, with a look of relief, blurted out something similar. A third said that he had seen how the fourth had struggled all throughout the previous legs of the nav-ex and had been instrumental in their team not getting lost in the dark. So when the fourth had initiated the negotiation, he simply supported him, almost as an acknowledgment of his previous efforts. The fourth, now clearly identified as the person who had thought of negotiation in place of a simple equal exchange, looked like he was caught in the headlights. What came out through his struggles to articulate his position was this: it became clear to him in the first couple of legs of the nav-ex that it was going to be a difficult challenge for their team, and he had felt burdened to lead his team successfully. The pressure had mounted on him as he kept hearing the joyous shouts of the others as their teams quickly found successive clues. So by the time his team arrived at the midpoint, well behind all other teams, he was ready to grab at any advantage to help his team members even out with the others, and had immediately suggested a hard negotiating stance for the exchange of clues. The realisation about the inappropriateness of his own suggestion had also hit him right away but by then he was caught up in that suggestion and had felt that he would let his team down if he now agreed instead for a simple exchange without any extra benefit for his team.

All throughout the latter part of the discussion something kept nagging at the back of my mind. I kept looking at the members of the tardy team, wondering why nobody had objected to something that they all were saying they did not agree with. My thoughts were on a leadership track, thinking self leadership and traits like assertiveness and risking stating one’s opinion. And then, as I kept worrying the thoughts, that ‘inspiring moments of clarity’ descended on me! I butted in into the discussion, referred to the time – we were close to midnight – and offered to state my thoughts which could perhaps begin to explain what was happening. I will try to crisply state the most significant ones here:

- Virtually everyone recalled feeling competitive at the beginning – this is typically influenced by the very nature of any nav-ex. So members of the tardy team were no different from others in that respect.

- That the team in question was late in arriving at the midpoint was a fact. And it is easy to understand how that must have weighed on its members, and influenced their decision making.

- The thought of negotiating was driven by the intention of doing good for the team and not by any individual’s personal gain.

- I think we all agree that each of the four team members were aware of how their stance of wanting to negotiate for a bigger share in the group’s achievement was incorrect, including the one who first voiced this approach.

- What I think was happening with this group is something that apparently happens with all of us at various points of times in our lives – the Abilene Paradox! In the present context, this is how it could be stated: groups and individuals frequently take actions in contradiction to what they really want to do and think is the best, and therefore defeat the very purposes they are trying to achieve. This affects group decision making in such a way that a team ends up taking a decision that is contrary to individuals’ understanding of a problem/situation. I sincerely feel that this is what was happening with this team of four, and anyone of us could have been in their shoes tonight.

- I requested the group to consider their experiences in the light of what I had said and decide for themselves if the Abilene Paradox did indeed help understand the behaviour of four of our group members. More importantly, this reflection will be able to help us be more effective in group decision making at our workplace.

In the article ‘The Abilene Paradox’, Jerry B. Harvey delves into the reasons why the paradox comes about for us at times, and ways to avoid it and cope with it if it does happen to our team/group.

This concept, the Abilene Paradox, is a very intriguing one, and goes beyond the concept of ‘groupthink’ where most of not all members of a group actually agree with a group decision even if it is not really the optimum one.

References:

- ‘The Abilene Paradox’ by Jerry B. Harvey

- Synopsis of the above article by Molly Doran in the NOLS Leadership Educator Notebook

* I refer to Syzygium cumini and a few other berries found during summer in the Sahyadri (Western Ghats) in the post here titled ‘Summertime Showers & Fruits of Labour’.

* For my post ‘Saying No is also a Decision’ click here.

Very interesting activity! Hesitancy in asking for help/advice from juniors is quite common in all organisations including the army. A close relative of Abilene Paradox is what we call in army as “Bhedchaal”. Which is basically following someone even though knowing he may be wrong with the attitude “Ki farak penda”!!

‘… quite common in all organisations…’ – so true, unfortunately. ‘Bhedchaal’ can also be dangerous in certain high-stakes circs. Ah well!